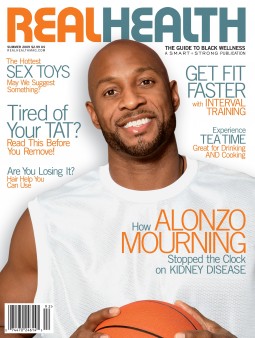

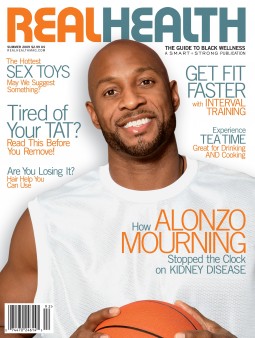

In 2000, Alonzo Mourning stood an imposing 6 feet 10 inches and weighed 260-plus pounds. He was a professional athlete at the top of his game. But even this formidable hardwood warrior couldn’t go one-on-one with kidney disease, a time bomb that makes African Americans nearly four times more likely than Caucasians to develop kidney failure (also called end-stage renal disease, or ESRD).

Like many people with kidney disease, Mourning was blindsided by news of his diagnosis. Many forms of kidney disease usually exhibit no symptoms until late in the course of the condition. And Mourning, who recently retired from basketball, fanatically guarded his health. “I was a person who relied so much on my health and strength to get me through my profession,” Mourning says. “I ate right, didn’t drink a lot, wasn’t a drug abuser—none of that.”

Ironically, just before his diagnosis, Mourning played a stellar season. He’d just pocketed a gold medal as a member of the 2000 U.S. Olympic basketball team, was named the NBA Defensive Player of the Year and made the NBA All-Star team—again.

So Mourning had no reason for concern, especially since early warning signs didn’t manifest in physical ailments—at least not obvious ones. “I felt a little lethargic and a little fatigued,” Mourning explains. “But I expected to feel a little run down because I’d been traveling all summer flying back and forth to Australia.” (Mourning had flown home to witness the birth of his second child, a daughter, Myka Sydney—named for the city where he struck Olympic gold—then had returned to the competition to resume playing.)

But then a preseason physical showed high creatinine levels in his blood, and the team physician sent Mourning to a kidney specialist, a nephrologist named Victor Richards, MD.

Creatinine—not to be confused with bodybuilding supplement creatine—is a chemical waste molecule generated from muscle metabolism and filtered through the kidneys; it increases in the blood if the kidneys become impaired for any reason. High levels of the substance warn of possible kidney malfunction or failure. Mourning’s doc recommended a biopsy.

Nevertheless, the sports star remained unfazed. “As a professional athlete, I’m so accustomed to just wrapping it up, throwing some ice on and getting back out there and just playing again—you know, that superhero mentality,” he says with a laugh.

“That’s exactly the way I felt,” Mourning recalls, “but this was something a lot more serious. When the biopsy result came back, it showed that I had a rare genetic disorder called focal segmental glomerulosclerosis [FSGS]. When I got the news, I was taking a nap in the middle of the afternoon.”

Mourning’s first question for the nephrologist had no trace of superhero bravado. “Am I going to die?” he asked.

Mourning says the nephrologist told him no, but hesitated when he said it. “The second question I asked him was, ‘Is there a cure for this?’ He said, ‘No. Probably in 10 to 12 months you’re going to be on a dialysis machine, then you’re going to need a transplant.’”

Then Mourning posed a third question. “Can I play basketball again?”

In answer to that query, Mourning’s nephrologist said since he knew nothing about what playing pro level basketball entailed that was entirely up to him. Mourning’s response was to get second and third opinions. In doing so, the basketball star found a world-renowned kidney doctor, Gerald B. Appel, MD, a clinical professor of medicine and nephrology at Columbia University Medical Center in New York City.

A disease that attacks the millions of nephrons, or filters, of the kidneys (the organ’s primary function is to remove waste products and excess fluids from the body), FSGS is characterized by scarring or hardening of the tiny blood vessels within the kidney. The result? Kidney damage that ultimately leads to the organ’s failure, which might occur rapidly or gradually.

While he weighed his options, Mourning immersed himself in research. “I educated myself,” he says. “I found out exactly what the disease was all about and what were the overall symptoms. I was very comfortable with what was going on in my body because I was knowledgeable about the process. It’s amazing how when you familiarize yourself with a disease how much more comfortable and confident you feel about attacking it.”

At Appel’s suggestion, Mourning chose an oral meds regimen to combat his disease. Appel thought they could slow the progression of the disease with this treatment. For a time, they succeeded.

As he followed his doc’s pharmaceutical strategy, Mourning found out just how expensive meds could be. Just one of his medicines, cyclosporin (a.k.a. ciclosporin)—an immunosuppressant drug—cost, without health insurance, a little more than $1,000 for a 30-day supply. “Immediately, I started thinking about all the other individuals, like working families, who have to pay for these drugs. So I started Zo’s Fund for Life in 2000, a program that operates under my foundation, Alonzo Mourning Charities.”

One of the goals of Mourning’s program, Zo’s Fund for Life Foundation (zosfundforlife.org), is to help people who can’t afford FSGS meds and to help raise funds for research and the education of doctors.

But Mourning’s new health regimen didn’t start and end with a doctor’s prescription. When his wife told him about a holistic doctor she knew, he listened. Eventually, after meeting the doctor, Kirby Hotchner, DO, Mourning grew to trust his medical expertise and introduced him to Appel. Together, the two consulted about Mourning’s treatment regimen. The physicians worked together to double team his kidney disease, despite their opposite medical approaches—a “very, very rare” occurrence, Mourning says.

“I think the key to my whole recovery was educating myself to natural alternatives—holistic medicine. That particular balance helped me out tremendously,” he says. “It helped me deal with the prescription medicines and their side effects.

“It’s amazing to me that doctors don’t tell their patients about alternative and holistic medicines and their positive benefits,” adds Mourning.

But kidney specialists have specific worries in regards to holistic treatments, explains Rulan Parekh, MD, a nephrologist and researcher specializing in cardiovascular disease and genetic risk of kidney disease. “As nephrologists, what we get concerned about with holistic therapy is that for much of the medications, vitamins and supplements, the kidney is the filter for all of these things. If you take an excessive amount of any sort of vitamins or any medications or any kinds of teas and things like that, then they can potentially adversely affect the kidney.”

Parekh stresses that, from a holistic viewpoint, a heart-healthy regimen—which includes being active, exercising, controlling blood pressure, watching one’s diet and not gaining huge amounts of weight—is key to treating kidney disease.

Because a heart-healthy regimen is also vital to treat kidney disease risk factors, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, Parekh also recommends people observe a common sense approach to health. “The best thing that people can do is to make sure they go for their annual visit, see a physician regularly and have their blood pressure checked,” she advises everyone.

The hope for the future, Parekh says, is that in five to 10 years, doctors will be able to prevent people from advancing to kidney failure, perhaps through genetic screenings. Optimistic about kidney research, Parekh cites the discovery of a gene, called MYH9, that is associated with nondiabetic kidney failure in African Americans.

Interestingly, the same gene is also associated with the type of rare kidney disease Mourning had, which eventually forced him to opt for a kidney transplant.

After his creatinine level escalated again, Mourning continued to play ball. Somehow he was still able to function at a high level on the basketball court. His doctors’ initial treatments had succeeded in halting the progress of the disease, but the final buzzer eventually sounded.

“What stopped me is when Dr. Appel told me, ‘Look, you’re at the stage right now where you might be feeling well, but your phosphorus levels are so high that if I let you go out there and play, you risk the chance of cardiac arrest.’”

Mourning insisted to his doctor that he felt good. He’d just had one of his best games since his diagnosis and treatment, he told Appel.

“Well, I still can’t let you do it,” his doctor shot back. “I just can’t do it.”

At that point, Mourning’s doctor suggested he start looking for a transplant donor. He told the dejected player that if he didn’t find a donor within the next two to three months, he’d have to put him on a dialysis machine.

“Ultimately, my second cousin on my father’s side—my father’s uncle’s son—gave me a kidney,” Mourning says.

The operation took place in December 2003. By summer 2004, after a grueling recovery, Mourning was back on the court dueling with his old rival Shaquille O’Neal.

A firm believer in the power of positive thinking, Mourning credits a large part of his successful kidney transplant to faith. “You’ve got to believe,” he says emphatically. “I know there’s a higher power that can heal all. Second, stay positive—a lot of people just don’t do that. They tend to feel very sorry for themselves, not realizing that, regardless of how bad things are, they could be a lot worse.”

Determined to chronicle his journey, which still continues, Mourning put his experiences in a book called Resilience: Faith, Focus, Triumph. “I created the book to help people,” he explains, “to encourage them to never give up, to help them tap into that resilience that we all have within us.”

Also a spokesperson for the National Kidney Foundation (NKF), Mourning emphasizes the importance of screenings and early detection.

“I encourage people to get regular checkups—at least once a year,” he recommends. “You can prevent something severe from happening before it escalates. Something could be going on. Diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol—all these [illnesses] are ‘silent killers.’ How often do we ignore symptoms—like lethargy, light-headedness, feeling rundown, memory loss? The list goes on. Or we find out that we have kidney disease and it’s something that we could have prevented if we went to the doctor, got a regular checkup, got our blood sugar evaluated, got our blood pressure measured.

“Those simple things can prevent disease,” stresses Mourning. “As a spokesperson for the National Kidney Foundation, I just let people know about the impact of these particular disorders on kidney disease. When I think of the more than 26 million Americans who are suffering from chronic kidney disease and millions more who are at risk, I say, ‘Okay, what can we do to prevent this?’”

Still faced with the reality that there’s a chance his body might reject the new kidney despite five years without a problem, Mourning remains upbeat.

“There’s always a 30 percent chance [of rejection],” he confirms. “I know that the further away you get from the actual transplant surgery, the less likely it is. But it’s important that you make the proper healthy lifestyle changes and stay consistent. I’ve made those adjustments. You have to be an active participant in your health. You can’t count on anybody else to do it.”

Point well taken.

Click here for our video interview with Alonzo Mourning.

On Borrowed Time

Unaware he had a rare kidney disorder, NBA legend Alonzo Mourning kept up the killer pace of an elite athlete. But as the shot clock ticked, he came closer and closer to becoming a kidney disease statistic.

Comments

Comments