The first two patients who received CAR-T therapy were still in remission a decade later, showing that the engineered cancer-fighting T cells can remain active in the body over the long term. Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research provided an update on the two cases in the journal Nature.

“This long-term remission is remarkable, and witnessing patients living cancer-free is a testament to the tremendous potency of this ‘living drug’ that works effectively against cancer cells,” study coauthor J. Joseph Melenhorst, PhD, of Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, said in a university press release. “Witnessing our patients respond well to this innovative cellular therapy makes all of our efforts so worthwhile, being able to give them more time to live and to spend it with loved ones.”

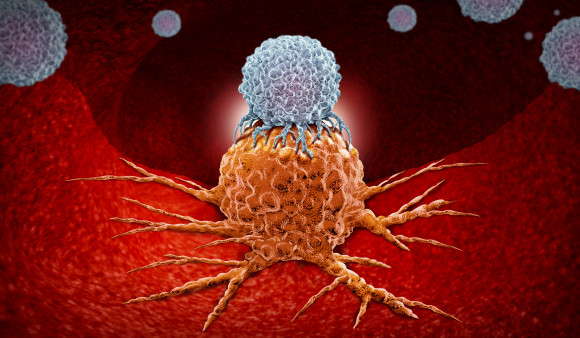

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy—better known as CAR-T—modifies a patient’s own T cells to enable them to better fight cancer. The treatment involves removing a sample of a patient’s white blood cells and using gene therapy to reprogram T cells with synthetic receptors that recognize a particular type of cancer. The engineered cells are then multiplied in a laboratory and infused back into the body. (In 2018, Cancer Health featured the advent of this new type of treatment in its first issue.)

In the summer of 2010, Doug Olson and Bill Ludwig were battling chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) despite receiving prior treatments. They joined a clinical trial evaluating tisagenlecleucel, a CAR-T therapy that targets the CD19 receptor on B cells. Both achieved full remission—Olson was cancer-free within weeks—and their cancer did not return, leading senior study author Carl June, MD, director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at the University of Pennsylvania, to say they were cured. Olson is still doing well; Ludwig, unfortunately, died of COVID-19 in early 2021.

Functionally active CAR-T cells remained detectable a decade later in both men—the longest persistence of engineered T cells observed to date. Speaking at a media briefing, June said he initially expected that the modified cells might last only a couple of months. What’s more, while the initial population of engineered cells consisted primarily of CD8 killer T cells, a population of CD4 cells later emerged and became dominant. In fact, both patients had almost all CD4 CAR-T cells after several years, suggesting that these cells—usually considered helper cells—have a previously unappreciated killer function.

Another milestone is on the horizon this year, as Emily Whitehead, the first child to receive CAR-T therapy to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), will celebrate being cancer-free for 10 years.

In August 2017, the Food and Drug Administration approved tisagenlecleucel, marketed as Kymriah, as the first CAR-T therapy, indicated for children and young adults like Whitehead with ALL; the approval was later extended to adults with large B-cell lymphoma. Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) was approved in October 2017 for adults with large B-cell lymphoma and later for follicular lymphoma. Three other CAR-T therapies have since been approved: Tecartus (brexucabtagene autoleucel) for mantle cell lymphoma and ALL in adults, Breyanzi (lisocabtagene maraleucel) for large B-cell lymphoma and Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel) for multiple myeloma. But this type of treatment still has not been approved for people like Olson and Ludwig with CLL.

Most patients treated with CAR-T cells do not respond as well as Olson, Ludwig and Whitehead, and researchers don’t fully understand why. The treatment can cause severe adverse effects, including cytokine release syndrome and brain inflammation. So far, CAR-T therapy is only approved for blood cancers, which are more accessible to the immune system, and the high cost of the labor-intensive treatment has limited widespread use. But doctors have already learned to manage CAR-T side effects, researchers are working to apply the approach to solid tumors and other diseases—including HIV—and economies of scale and market competition could bring down the cost.

“Penn has begun testing next-generation T cells in more blood cancers, including lymphomas, and against the challenging solid tumor cancers,” June said. “A considerable amount of deep learning goes into studies that will fine tune the way cancer patients are treated with CAR-T cells, and we look forward to the next phase of research and enhancements, including how best to use this approach to target other cancers and diseases.”

Click here to read the report in Nature.

Click here for more news about CAR-T therapy.

Click here to learn more about immunotherapy for cancer.

3 Comments

3 Comments