Ed RandallCourtesy of Ed Randall/Fans for the Cure

Baseball fans may recognize Ed Randall as a longtime broadcaster for the sport commonly known as America’s favorite pastime. But since 2003, he’s been speaking out—and enlisting athletes, from minor leaguers to four-time Gold Glover Steve Garvey—to promote the lifesaving value of early detection for prostate cancer. That’s the year he founded and became CEO of Fans for the Cure (FFTC).

Randall became a household name when his television show Ed Randall’s Talking Baseball was broadcast on over 20 regional sports networks nationally from 1988 to 2002. He currently hosts the weekly Saturday morning show Remember When with former Red Sox star Rico Petrocelli on Sirius/XM’s MLB Network and Sunday morning’s Ed Randall’s Talking Baseball on New York’s WFAN.

But his world turned upside down 20 years ago when he received a prostate cancer diagnosis at age 47. He knew almost nothing about the disease and soon realized that many men faced the same quandary. So he set out to change that. Randall recently spoke to Cancer Health about FFTC’s work and how he’s managed to bring his two worlds together to make a difference.

First, let’s just start off with your story. How did you get involved in baseball broadcasting?

Growing up in the Bronx, baseball was the only sport that I could play half decently. In school pictures, I was always in the front because I was small. The basketball net seemed like it was way up, and as for football, I couldn’t grasp the idea of knocking down another human being or, far worse, having him knock me down. With regard to hockey, the closest that we got to ice in the Bronx was seeing ice cubes in our parents’ cocktails.

I just loved listening to baseball on the radio and on television, but especially on the radio. When I was playing ball in my teens on some very good teams, I was a pitcher. When I wasn’t pitching and I might be playing center field, I’d actually be doing the play-by-play of the game to myself. I was doing play-by-play waiting for the D train to go to school. I was doing play-by-play all the time. That’s what I wanted to do.

When I graduated from high school, I went to Fordham University [in the Bronx]. On the first day of orientation, the leader happened to be the news director of the very successful radio station at Fordham University, WFUV, which has given the world Vince Scully, Charles Osgood and Alan Alda. I walked up to [my orientation leader] and said, “How do you join the radio station?” He said pretty much what Woody Allen once said, “Ninety percent of life is just showing up.”

And so I did, and for the next four years at WFUV, I talked on the air. I got a chance to do my baseball play-by-play of the college team. That’s how I got started: college radio.

Can you talk about your personal experience with prostate cancer?

I was 47 years old at the time that I went for my routine annual physical—or at least I thought it was going to be routine. And my general practitioner called me the next day. He had never called me before. He goes, “Ed, your PSA is really high.” [Editor’s note: Prostate cancer can be detected by a blood test that measures prostate-specific antigen (PSA), a protein produced by the prostate gland.]

I had been broadcasting for a number of years, and my only definition of PSA was “public service announcement.” I had no idea that it could be an indicator of cancer. He said, “Maybe the lab screwed up. Come back and let’s take another blood test. We’ll send it to another lab.” So I did, and the results of the second test were exactly those of the first. My PSA was very, very high. I was filled with cancer. Then, through God’s grace, I got—what I like to say, using a baseball metaphor—a second at-bat in life.

I had the implementation of radioactive seeds that ate the cancer eventually. Then, when I went into remission in 2000, I came to the realization that there could be tens, hundreds, thousands or millions of men out there like me walking around feeling like they’re fine, thinking they were fine, when in fact they were time bombs because prostate cancer in its early stages has no symptoms. I said, “You know what? We got to get to these guys.” So I started Fans for the Cure.

What are the goals of Fans for the Cure?

More than anything else, it’s about educating men to let them know that there is an almost 100 percent survival rate if prostate cancer is detected early, and I’m one of those lucky guys. That a simple blood test could save their lives. That is very important to us.

We are in the space of education and awareness. We would like to also get involved in research. But right now, having been in this space for so long we feel that we’ve developed a niche.

We’ve been an official charity of Minor League Baseball for over 12 years. We’ve been in more than 1,000 ballparks with local volunteers handing out our materials. This is the largest health care initiative in the history of Minor League Baseball.

We’ve got to get out there, get to these guys and tell them that prostate cancer is not a death sentence. It is survivable, as there are 3 million prostate cancer survivors walking around in the United States right now.

You talked about how there is a high cure rate for prostate cancer when detected early. What are some of the obstacles that prevent men from early detection?

Women go to the doctor. Men look for excuses not to go. We have rubber bracelets that say “Fans for the Cure.” The lettering is in pink because women are the caregivers. They’re the ones who kick men in the butt and tell them to go to the doctor.

You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make them drink. It’s really distressing. Men need to understand how easy this process is. The main impediment is getting them in the door to consult with their doctor yearly.

How does FFTC work to break down that reluctance?

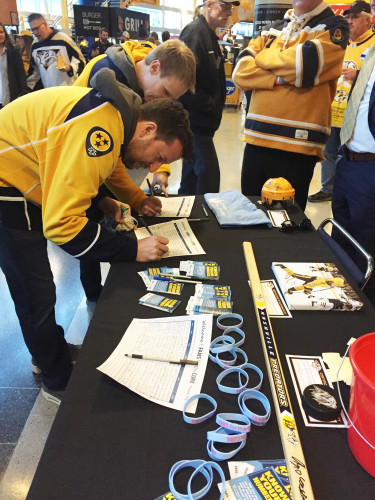

If the men won’t go to doctors, we’re going to bring doctors to them. We recently held a free prostate cancer screening in Nashville before and during the game of the Nashville Predators of the National Hockey League. This is what we need to do. We need to be out in the community, especially in the underserved or, as I like to say, unserved minority communities.

Particularly in the African-American community, where prostate cancer is ravaging African-American men. We’re not waiting for them to go to the doctor. We want to be able to establish a network of African-American churches and barbershops. One in six are going to be diagnosed with prostate cancer. We want to try to do everything to reverse that. [Editor’s note: The overall risk of developing prostate cancer is one in nine.]

Prostate screening signage by Fans for the Cure at Nashville Predators hockey game.Courtesy of Fans for the Cure

National Predators hockey fans at a Fans for Cure table.Courtesy of Fans for the Cure

You mentioned that the Black community is disproportionately affected by prostate cancer. How is Fans for the Cure working to combat that?

We spoke a lot about getting involved in the African-American community, and now is the time to do it. We did a prostate cancer screening at Vanderveer Park United Methodist Church, a very influential African-American church in Brooklyn, at the end of March. They invited other churches and their congregation to participate.

We want to dive into the minority communities as much as we possibly can. It’s tragic when I see a man from the African-American community—any man, actually—pass away because he just simply didn’t take care of himself.

Ed Randall talks to African-American men about prostate cancer in Brooklyn, New York on March 30.Courtesy of Fans for the Cure

Former NBA player Ken Charles with Ed Randall at Fans for the Cure event on March 30.Courtesy of Fans for the Cure

There is often confusion surrounding screening recommendations for prostate cancer that both patients and clinicians face. How does that affect early detection, and what do you think can be done to fix that?

The government did us no favors in 2012 when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force decided to issue a recommendation downgrading the use of the PSA test and then upgrading it somewhat in 2017. Unfortunately, that gave men another reason not to go to the doctor. We need to get the biggest megaphone possible to tell men that they’re loved, wanted, needed and cherished. That they have a responsibility to go to the doctor not only for themselves but also for their loved ones. [Editor’s note: The U.S. Preventive Health Task Force had recommended against routine PSA screening for men ages 50 to 70—and African-American men ages 45 to 70—but later walked that back to advise that men make a decision about PSA screening on an individual basis with their doctors.]

We have to fight through this. We have an esteemed medical advisory board of 35 of the greatest cancer doctors in this country. All of them are foursquare behind the importance, relevance and effectiveness of the PSA test. We rely on our advisory board to also help us spread our message.

You mentioned how prostate cancer not only affects men but also their spouses and families. What else do you think can be done through women to help encourage early screening?

We want to establish a women’s advisory board within the charity to be able to encourage men in general to go to the doctor. We want everybody involved. This is not just a men’s disease.

We had a fundraising gala two years ago. We invited a woman to speak whose husband suffered with prostate cancer for 10 years before passing away at the very untimely and premature age of 54. She got up to speak in front of 440 people and said, “When John got prostate cancer, I got prostate cancer.” I can’t put it any better than that.

You’ve enlisted many sports stars for your campaign. What are you hoping to achieve with these celebrity athletes?

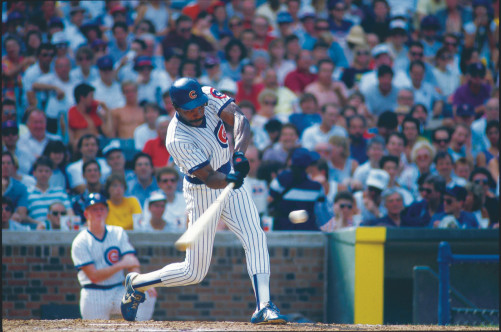

People are going to pay attention when Hall of Fame baseball players like Carlton Fisk, Andre Dawson or Phil Niekro speak up about prostate cancer. We welcome that. We have 128 former athletes from various sports who themselves have been affected by prostate cancer (or members of their family have) on what we call our Legends for Life Advisory Board.

This is a blessing from God. For so many years, I met these people on the playing field and covered them as a reporter and anchor. Then, I got diagnosed with prostate cancer and started this charity. Later on, these guys get diagnosed with prostate cancer. So there’s this familiarity with me and my work and trusting me.

It’s very important when these guys speak and talk about their experiences because of their fame and the fact that other men are going to listen to them because they’re fans of these guys from when they were on the playing field.

You must have some interesting stories about some of these star athletes.

One story that comes to mind is Clark Gillies, the Hall of Fame New York Islander hockey player who was this big strapping 6-foot-3-inch, 220-pound guy that nobody messed with when he was playing. He won four Stanley Cups with the Islanders. We were on the phone for over an hour after he was diagnosed. Basically, he was saying, “I’m the strongest guy in the world. How the hell could this happen to me? This is crazy.”

And then, Dusty Baker, longtime baseball manager. When he was diagnosed, he was the manager of the San Francisco Giants. I called him. We were on the phone for over an hour as well. He was really distressed.

There was also Andre Dawson, baseball Hall of Famer. I had found out about him being diagnosed with prostate cancer and asked him if he would be on the advisory board. He said, “Absolutely.” He was working as an adviser for the Miami Marlins. I was touring spring training camps, and I was [going to] Florida to speak to the team.

I see Dawson, who I didn’t expect to see. Before I go out there to talk to 150 players, he says to me, “Today’s the day.” I said, “What do you mean?” He says, “I’m going to tell everybody today. After you finish talking, I’m going to talk.” So I talked, then I introduced Andre. He told the entire Miami Marlins organization that day that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer. There was a very dramatic reaction to that. [Click here to view a slideshow of baseball stars who have joined the FFTC cause.]

Andre DawsonCourtesy of Fans for the Cure

For several years, FFTC has worked with Minor League Baseball to encourage PSA testing and early screening. What do you have planned for this year in collaboration with the league?

We’re going back to Minor League Baseball for our 13th season. We will hand out thousands and thousands of pieces of material that promote prostate cancer awareness and education and getting to the doctor.

FFTC has been most associated with early detection, but it has recently joined forces with the Metastatic Prostate Cancer Project (MPCP), an organization that is enlisting men with metastatic prostate cancer to anonymously donate saliva and blood samples to create a comprehensive database for researchers. Can you tell us about this venture?

We want to expand our footprint, and we’re very grateful for this association with MPCP. They’re doing great work. Among our doctors that are on our medical advisory board, we have a few that are very esteemed with national reputations involved in late-stage prostate cancer. We thought that this would be a natural extension for us when the Metastatic Prostate Cancer Project people reached out to us, saw the work that we did and said, “We’d like you to align with us.” The association is new. Whatever strategy is going to arise out of this, we told the MPCP people that we are there for them with whatever it is that we can do to help their patients.

Any advice to men out there who are newly diagnosed with prostate cancer?

Come to us. We do hospital and doctor referrals. We want men to understand that they’re not alone. You can come to us should you seek a second opinion or whatever you believe that will help you get through this.

Women talk to each other. Men do not. I speak from personal experience. When you get diagnosed, this wall comes down in front of you. I am looking forward to hearing from any man concerned about prostate cancer who needs somebody to talk to. We just want them to know that we’re there for them.

What are some of your other future goals in regard to FFTC?

To save as many men’s lives as we can. When I speak in spring training, I tell the players I’m the only CEO you’re going to meet who hopes to go out of business. I hope that there will be a cure for prostate cancer on those days that I speak to those players before they get off the field. Until then, I will be the car alarm you can’t turn off—telling men that they’re loved, wanted, needed and cherished and that they have a responsibility to go to the doctor.

Comments

Comments